Proofread Your Nonfiction Book with These Proofreading Tips for Authors

Congratulations! Your book has emerged from the editing and design/layout stages. You have an electronic or printed copy of the page proofs.

By now, you’re counting down the days until your book is officially in readers’ hands. But it may not be time to coast just yet. Anyone who’s wiped out on their new BMX bike—on their birthday . . . while riding down a hill . . . with no one else around—has learned that lesson the hard way. Gulp.

Now it’s time for proofreading.

Implement these helpful proofreading tips so you can land the jump, race down the final stretch, and celebrate in style.

What Is Proofreading?

Proofreading is a surface-level reading and quality-check of already-edited text. It takes place after the designer has prepared the text for publication.

Proofreaders ensure that the layout and formatting is correct and consistent and identify typos and errors of spelling, punctuation, and grammar that the author, editor, and designer somehow missed.

Proofreading vs. copyediting

What is the difference between proofreading and copyediting?

Copyediting takes place before the book goes to the designer. Proofreading takes place after. Proofreaders look for remaining errors or inconsistencies caused by the author, the copyeditor, the designer, or the file format conversion process.

Yes, copyeditors look for typos. Yes, they fix problems with grammar, spelling, and capitalization and help with formatting. But copyediting takes place before the design stage. Copyediting is broader: it also involves reworking some of the text and resolving repetitive, inaccurate, or inconsistent words and sentences.

Proofreaders will not necessarily compare proofs to the pre-designed copy. A cold reading (or blind reading) of the proofs is usually adequate.

**Some people (mis)use the term “proofreading” when they really mean any last-minute checking of text, at any stage of the writing or publication process. You may find these tips useful even if you’re not checking final page proofs or e-book files.

Tips for Proofreading

Have a style sheet and refer to it. A style sheet is a list of stylistic choices that reveals how the book standardizes its use of abbreviations, numbers and dates, punctuation, capitalization (including a.m. and p.m.), hyphenation, spelling, italics, bibliography and note style/formatting, and acronyms. If your book has been professionally copyedited, you should have a style sheet.

Remember what proofreading is. You should rarely be rewriting or rearranging sentences. You should be marking the necessary final corrections.

Use a checklist. There’s no perfect, exhaustive checklist, but having one standardizes and streamlines the process. Try looking at the surface-level things before looking at the fine details.

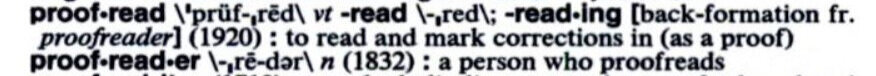

Proofreading symbols (also known as proofreaders’ marks), from Figure 2.6 of The Chicago Manual of Style, 17th edition. (Click here to download the image.)

Clearly indicate the necessary corrections. Log them in a Word or Excel file. Some of my clients also write corrections (in colored ink) on an electronic or printed page and scan and send those corrections to the designer. Here’s a list of proofreaders’ marks.

Don’t proofread alone. Because we’re so familiar with our own writing, we’re likely to gloss over parts of it. When facing deadlines and distractions, we rush. We get overwhelmed. And we make mistakes. Get help.

Minimize potential errors by utilizing beta readers. A beta reader is an avid reader in your genre who will do the job of a proofreader (and sometimes some light copyediting) on a tight deadline. Beta readers can be fans of your work, gifted (and properly paid) college students or graduate students, or colleagues.

Beta readers typically enter the scene during the final editing stage. They often get a free final copy of the book as compensation. Some of my clients, and many academics or academic publishers, (offer to) pay beta readers a small amount.

Learn more in my article, “How to Successfully Use Nonfiction Beta Readers.”

Do what it takes to get the most accurate results. Start immediately and take your time. Don’t rely heavily on often-inaccurate software tools. Mark only necessary edits. Some designers and traditional publishers may charge a fee for excessive corrections. If you must, pay the overage fee and don’t allow that to happen again in the future.

Consider hiring professional help and budget accordingly. A rate of $3 to $5 per page for fiction, at 8 to 14 pages per hour, is common for fiction books, and $5 to $7.50 per page, at 7 to 11 pages per hour is common for nonfiction, says the Editorial Freelancers’ Association.

Average proofreading rates vary by genre, difficulty level, and proofreader experience.

and be sure to check your work twice! You got this!