The Lyttelton Expedition of 1759: Some Thoughts

While doing some research on South Carolina colonial governor William Henry Lyttelton, I found myself revisiting the French and Indian War in South Carolina by looking more closely at that colony’s ill-advised and ineffectual 1759 expedition against the Cherokee Indians.

It was the first of three campaigns against the Cherokees during the French and Indian War. I wrote about it in chapter 4 in my book Carolina in Crisis.

Background to the “Lyttelton Expedition”

After a series of Cherokee revenge killings on the southern frontier, Governor Lyttelton detained Cherokee diplomats who had come to Charleston (then Charles Town) to discuss their grievances.

Lyttelton raised an army consisting mainly of militiamen and marched the army (and the detainees) across South Carolina to Fort Prince George. The fort, opposite the Cherokee village of Keowee, was in use from 1753 to 1768, and is today under the waters of Lake Keowee. The governor forced a handful of Cherokee leaders to sign a treaty.

map from Alan Calmes, “The Lyttelton Expedition of 1759: Military Failures and Financial Successes,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 77, no. 1 (January 1976): 10–33.

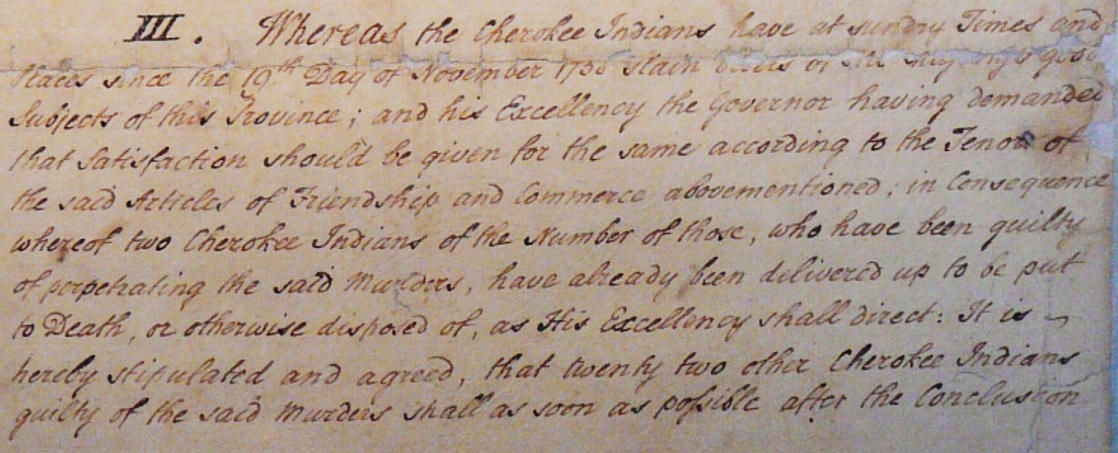

The treaty stipulated, among other things, that 22 Cherokees would be held at Fort Prince George until Cherokee “murderers,” accused of the revenge killings of white settlers, would be delivered up in their place.

While this treaty of December 26, 1759, triggered two years of hostilities that shook Carolina and Cherokee society, the campaign was, on the surface, less eventful than the two expeditions that followed.

No shots were fired during the expedition. However, the soldiers brought smallpox home with them to South Carolina. And the hostage-taken created a crisis of epic proportions, as revealed in Carolina in Crisis.

image from a copy of “The Treaty of Peace and Friendship,” signed at Fort Prince George, December 26, 1759. Treaties with the Cherokees, 1759–1777, South Carolina Department of Archives and History, S131005.

A Closer Look

I reexamined the available muster rolls (South Carolina Department of Archives and History (SCDAH) in Columbia, and transcribed in Colonial Soldiers of the South); issues of the South Carolina Gazette newspaper; assembly and council journals; Soldiers and Uniforms by Fitzhugh McMaster; and Lyttelton’s papers (Clements Library, University of Michigan, and on microfilm at SCDAH), and here are some observations. . . .

Future South Carolina Patriots

Future patriots Christopher Gadsden and Francis Marion served with the “gentlemen volunteers.”

William Moultrie was one of Lyttelton’s aides-de-camp.

Militia officers included future revolutionaries Richard Richardson, George Gabriel Powell, and William “Danger” Thomson.

Disease and Desertion

There were never more than 1,700 men in service at a time, 1,300 of them “fighting men” and the rest servants, slaves, and wagoneers. That number could have been much higher if not for disease and desertion.

Measles, respiratory illnesses, intestinal illnesses, and eventually, smallpox, posed a grave danger to the troops’ health. These men, many of them the poorest of the poor, were under-supplied, averse to military discipline, and perhaps feared leaving their families alone.

There are approximately 170 deserters listed by name in the available records.

Richard Richardson Sr., ca. 1770. Private collection. Richardson died in 1780 and is buried in Rimini, SC.

From the small militia detachments from Granville, Upper Berkeley, and Colleton counties, 20 men deserted. From Colonel John Chevillette’s Upper Berkeley County battalion, at least 23 men deserted. (Records are incomplete.) From Richard Richardson’s Upper Colleton County militia battalion, 27 men deserted. From George Gabriel Powell’s Upper Craven County militia battalion, roughly 100 men deserted, including 4 officers.

In Powell’s battalion, one company lost 18 of 28 men to desertion; another 9 of 40; a third 10 of 72. Captain John Hitchcock was one of 16 men in his 24-man company who deserted. The unpublished assembly journals of 1761 reveal that he paid a £300 fine by liquidating his assets and selling his boat and five enslaved people. He unsuccessfully petitioned the assembly to overturn his fine.

Indians and Free Black Men

The expedition included 8 Catawbas and, for a time, 27 Savannah River Chickasaws. The latter were recruited and led by Ulrich Tobler, a Swiss man from New Windsor Township. “Indian Tom” and “Indian Charles” were with the Granville County militia detachment commanded by Captain John McPherson. A notation next to their names says “Port Royal.”

Free men of color were eligible to serve in the colonial militia. Several of them served in the Lyttelton expedition: teenager James Ashworth, in Captain James Leslie’s company, Colonel Richardson’s battalion; future frontier outlaw Winslow Driggers, in Captain Alexander McIntosh’s company, Colonel Powell’s battalion; John Graves, with Driggers in McIntosh’s company, Powell’s battalion; and Thomas Chevas, a deserter from Capt. John Hitchock’s company, Powell’s battalion.

The assembly journals (October 4, 1759) reveal that these soldiers of color would have made 7 shillings per day, South Carolina currency. The typical white militiaman made 8 shillings per day. Soldiers with skills as carpenters, wheelwrights, blacksmiths, gunsmiths, or harness-makers earned additional pay.

Who Else Accompanied Lyttelton’s Army?

Lyttelton’s army included slaves, and servants to clear the road and take care of the horses and wagoneers. There were “hunters,” “butchers,” and men gathering wood and water. There were at least 5 drummers. Four men were hired to drive two 3-pound iron field pieces and two 4-pounders.

Several dozen Cherokee detainees with the army—led by Oconostota of Chota, the highest-ranking Cherokee warrior—were under armed guard.

Sixty colonists from Rocky-River and twenty-five from Long Canes also joined the expedition.

The rector at St. Bartholomew’s Parish, Rev. Robert Baron, was in Captain Samuel Elliott’s Colleton County militia detachment.

Future revolutionary Andrew Pickens does not appear on any muster rolls and apparently did not serve in the expedition.

P.S. If you’re looking for names of the South Carolina militiamen who were part of this expedition, you can find those in Murtie June Clark, Colonial Soldiers of the South, 1732–1774 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Col., Inc., 1986).

Clark transcribed the original pay rolls and muster rolls in the South Carolina Department of Archives and History in Columbia. I think these are also in the Early State Records microfilm (available at the Library of Congress, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, and CRL Libraries).

Many of the men in Lyttelton’s retinue are only mentioned in the South Carolina Gazette, the assembly journals or council journals, or the William Lyttelton Papers at the William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan (microfilm copy, South Carolina Department of Archives and History).

A list of the gentleman volunteers under Christopher Gadsden has been printed in The Writings of Christopher Gadsden, edited by Richard Walsh (Columbia: The University of South Carolina Press, 1966), 12–13, but it is a poor transcription. The original is in the William Lyttelton Papers, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, box 12 (microfilm copy, South Carolina Department of Archives and History).

I have never seen the names for the Catawbas and Chickasaws who were, for some time, with the army.