10 Ways Editing and Typing Have Changed since the 1st Edition of The Chicago Manual of Style and the Era of the Typewriter

If you’ve somehow crawled out from under a rock, dusted off the old typewriter you used in the ’80s, and started typing again—or maybe you just haven’t been paying close attention or reading a lot of really old books—you might not know that writing “style” and editorial standards have evolved.

(In this case, you probably need a copyeditor!)

As a copyeditor of nonfiction manuscripts (also known as a copy editor), I often see some of these older conventions—especially when those manuscripts draw heavily on older sources or are written by people who used typewriters years ago. (Psst: That’s a nice way of saying, err, AARP-eligible Americans.)

The Chicago Manual of Style, the preeminent guide to American English copyediting (also spelled copy editing) and typesetting, has gone through eighteen editions since its first in 1906, and the shift from typewriters to computers has brought additional changes.

Scroll down to read about how such things as hyphenation, writing dates, dashes, capitalization, abbreviations, using Roman numerals, ibid., spacing between sentences, quotation marks, and writing Jr. and Sr. have changed over the years!

Want to find a copy editor for your nonfiction manuscript?

Here are 10 ways that style and editorial standards have evolved over the years:

1. Words and compounds are less frequently hyphenated.

Remember that Jerry Lee Lewis classic, “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On”? Well, once upon a time, there was a whole lotta hyphenatin’ goin’ on too. But just like beehive hairdos and go-go boots, that trend has faded into the groovy mist.

Many words that were once hyphenated when they were relatively new terms are now “closed compounds.” For example, e-mail is now email, and pay-roll is now payroll.

Other compounds that were once hyphenated have now lost the hyphen. That means cross-section is cross section, post-office is post office, and ice-cream is ice cream, regardless of whether those are nouns or adjectives.

➡️See my “Complete Guide to Hyphens.” or the hyphenation guide in the 17th edition of CMOS.

Additionally, words with double vowels were once hyphenated but no longer are, such as co-operate. Now the word is closed up: cooperate.

The obsolete advice appears below.

From page 33 of Manual of Style.

2. Month and year are no longer separated by a comma.

For a time, you would write November, 1905, but now it’s just November 1905. Here’s the outdated advice on how to write dates:

From page 52 of Manual of Style.

3. Probably because most people no longer type on typewriters, which have a limited number of keys, the em dash has replaced the double hyphen.

In other words, -- is now—. The em dash has replaced the double hyphen in modern American usage. (See my popular blog posts on the em dash and the en dash.)

4. Downstyle capitalization, as it is called, is now the preferred style. If in doubt, don’t capitalize!

American English has been moving for more than a century to reduce capitalization. In the eighteenth century, it was not uncommon for nouns to be capitalized.

And for quite a while, the commonly accepted convention was to capitalize nouns when it was known who or what the nouns were referring to: “the Bay” or “the General,” for example.

Most authors still have a tendency to overcapitalize, seemingly unaware of Chicago standards.

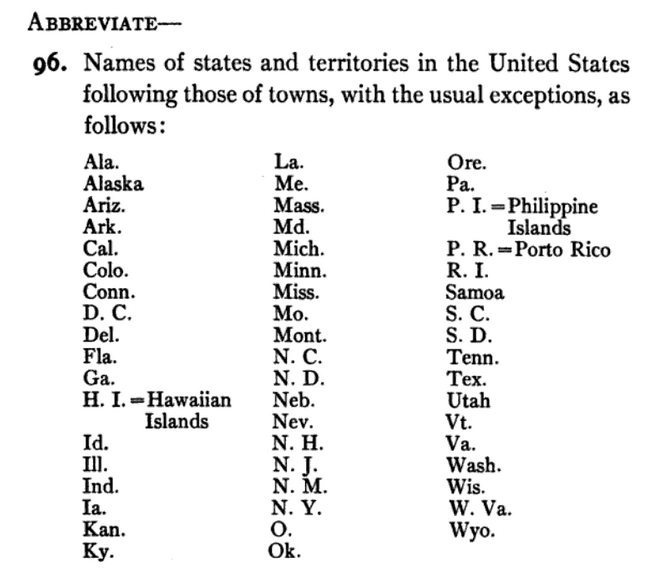

5. Over time there has been a trend towards less abbreviation.

Abbreviations have changed. Several decades ago, US states (and often book bibliographies) used US postal abbreviations such as Conn. for Connecticut and Mich. for Michigan.

The Chicago Manual of Style calls for modern abbreviations to be used. I believe it says that traditional state abbreviations are permissible, though they are far less frequently used.

Also, Ph.D. is now PhD. Even US was once commonly written U.S. or U. S. A.

The old advice appears below. You’ll see that some abbreviations even had spaces in them (N. C., N. D., and so forth).

From page 33 of Manual of Style.

6. Roman numerals are now rarely used in books and bibliographies.

Roman numerals are no longer used in chapter headings and volume numbers.

It used to be that chapter titles and volume numbers were typically written as roman numerals. Now, that is not the case.

It is not Chapter IV but rather Chapter 4.

From page 72 of Manual of Style.

7. Ibid. is now discouraged but permissible.

Effective in 2017 in its 17th edition, “in ... departure from previous editions, Chicago discourages the use of ibid. in favor of shortened citations” (See pages 757–58). The reason given is to avoid confusion with electronic sources. If you were to skim a book or a chapter, read an excerpt, click on an endnote, and see “Ibid., 56" you might be confused as to what “Ibid.” was referring to, but if you saw “Morrison, 56,” you wouldn’t be as confused.

These days, Ibid. is not italicized.

Ibid. is the abbreviation of the Latin ibīdem, which means “in that very place” or “in the same place.”

And Now, Some Typewriter-Related Things to “Unlearn” in the Age of Computers:

8. It used to be that most typists put two spaces between sentences. The standard is now one space.

Separate sentences with one space. This is because computer word processing programs (as typeset books have done for years) use proportional type. As this article from Aeonix explains, “On (most) typewriters you have a fixed-width typeface. To get a reasonable distinction between word endings and sentence endings, you need to have two spaces. When you are typesetting a document, you are using proportional type. Each letter has its own width and space around it. The punctuation marks are also designed with the appropriate space.”

9. “Smart quotes” or “curly quotes” are now used, rather than "straight quotes" aka "dumb quotes."

See how the quotes are curved rather than uncurved? Quotes and apostrophes should be curved. Typesetters had always inserted curly quotes when setting books, but typewriters, with limited space for keys, had quotes and apostrophes that were the same whether at the start or the end of a word.

Humor me for a second while I share some important reminders:

Use an apostrophe pointed the right way—the closing single quote—in these situations: ’tis, ’80s, Go get ’em!

When writing feet and inches, and in mathematical equations, use the prime or double prime symbol, not a curly quote or a dumb quote. This is the prime symbol: ′ and this is the double prime symbol: ″

Here’s an example: “London is located at 0° 7′ 5.1312″ W longitude.”

10. Jr. and Sr. are now typically written without commas.

CMOS has recommended since its 14th edition in 1993 to drop the commas after Jr. and Sr.

It remains permissible, however, and you’ll notice that many people write their names with commas.

Keep these things in mind, and you’ll produce a much more polished manuscript.